Software, science and the age of digital discovery: Q&A with Nathan Johnson

Nathan is a senior software developer and scrum master at Eagle Genomics. In this article he discusses the rapidly expanding role of software solutions in enabling ground-breaking scientific discoveries.

Q: What is your role at Eagle Genomics?

I am a scrum master for the Knowledge Discovery team. Our team is focused on delivering features which link Eagle’s knowledge graph database (our life sciences data catalogue) to our platform’s user interface. The team builds data visualizations which help users explore and visualize life sciences data within the e[datascientist] platform. As a scrum master I’m involved with coaching people in the team and encouraging them to follow Scrum and Agile principles. I’m also a senior software developer, so I write code, just less than I used to because I’m now involved in software architecture too!

Around 50 percent of my time is taken up with high-level design and architecture as well as Agile processes. The rest of my time is spent reviewing code from the members of the team, making sure that we’re following best practice and standards which encourage a progressive software development process.

Q: As a developer, how do you bring software solutions and the life sciences together in your work?

I come from a bioinformatics background and originally trained as a biochemist, so I was also in a wet lab for a while. I then moved into bioinformatics before making the move to software development.

My background has mostly been in infrastructure development to support bioinformatics rather than data analysis. I used to work as a lead developer for the Ensembl database in the regulation team at EMBL’s European Bioinformatics Institute. Having that experience and the understanding of the context our users work in gives me a really useful insight into what users want and need.

Q: What is the role of software in the digitalisation of life sciences R&D and how does it impact the way science is carried out?

Science is evidence based and evidence in science is essentially data, but just having data is almost useless! In and of itself you don’t get a lot out of it, you have to do something with it to make it useful. What software enables us to do is transform that data into information and knowledge. Researchers can look at disparate pieces of data and might be able to join some of the dots themselves but software is capable of spotting multiple connections quickly and accurately where the human eye simply can’t. What we’re doing at Eagle Genomics is enabling transformation of data into knowledge. By stitching together disparate pieces of information within enterprise organisations, such as internal databases and research results, and applying an artificial intelligence (AI) approach on top of that, our platform enables researchers to make new discoveries which they couldn’t previously identify without the power of AI.

Q: For you, what is the most important factor in building a successful software solution and why?

The most important thing about building a piece of software is meeting the requirements. It is critical to keep requirements at the centre of the planning process and user stories and to ensure those requirements are verbalised and formalised within a development team. That’s an intrinsic part of the Agile process we use at Eagle and allows a developer to very quickly deliver something which meets a specific set of requirements. Complementing this are non-functional requirements such as performance and how easy it is to shape code. These are the long-term qualities that enable a successful solution. Keeping these key factors in mind means that a developer won’t build something that becomes redundant two months later because they’ve coded themselves into a cul de sac!

Q: How is the software used in Eagle’s e[datascientist] platform enabling researchers and organisations to make novel scientific discoveries?

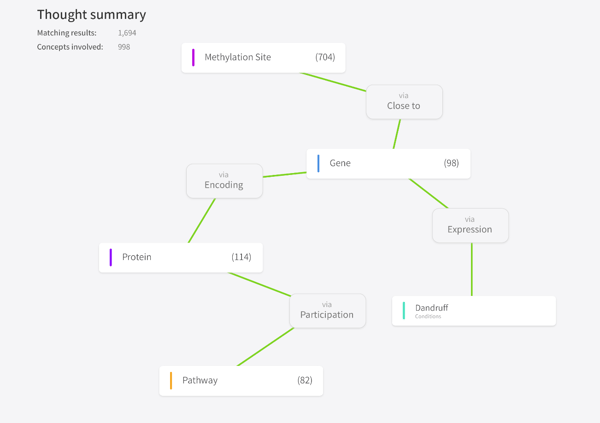

One of our initial versions of the platform was very open in terms of how we enabled users to explore data. In the first iteration we built an interface allowing users to create a knowledge graph by visualizing connections between different data entities. This alpha version of the display enabled users to literally connect the dots between disparate data objects in an internal database with other reference data from a variety of multi-dimensional open access datasets.

Screenshot of alpha knowledge graph

Screenshot of alpha knowledge graph

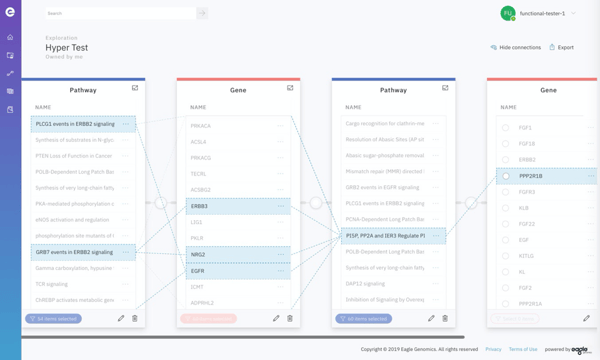

In that iteration it was very obvious that a user was creating a graph across datasets - it was very powerful and allowed lots of different elements to be brought together and for AI to be applied across them. This is still our underlying technology and we still use the knowledge graph, but a more recent feature we have developed focuses the user interface around a specific use-case, which we call ‘Exploration’.

This interface simplifies the process and helps guide users into a pattern of behaviour which will enable them to follow the most relevant entity relationships rather than having to choose from every single possibility!

Screenshot of Exploration functionality

Screenshot of Exploration functionality

Q: In the future, how do you think the role of software will evolve in scientific research and discovery?

I think using technology is going to become mandatory in most job roles. As coding languages become more finessed, software is certainly going to creep into less traditional domains. People’s skill-sets will have to broaden given the evolving environment they will be operating in. However, I also think there will always be a place for dedicated software developers but the roles and environments in which people are using software will broaden significantly.

Something which I think will become more common-place, which you can already see in voice enabled assistants, is that AI devices will become medical. For example, I think we’ll eventually see devices which will be able to monitor epigenomic profiles on a daily basis, or toothbrushes which will be able to read the oral microbiome. I’m very much looking into the future, but you’ve got to think big!

Q: Where do you do your best thinking?

Sometimes I think it’s when I’ve just woken up, but then half an hour later I really change my mind! Quite often, when I have a particularly vexing programmatic problem, I go for a walk in the woods and that helps! Sometimes it’s just on the bus, when I’ve just got a bit of space to stare out of the window and let my mind wander without pushing too much.

![Learn more about e[datascientist]](https://no-cache.hubspot.com/cta/default/2869527/95a273e6-3721-4619-96f8-c62aaf8fade1.png)